It could be true for most people that later life is grounded on childhood experience. At seven, George enjoyed the country lanes of sometimes sunny Cornwall, ambling back and forth each day, between high hedgerows, to a tiny village school about a mile from home. He was excited by the world around him, and it seems likely that those early encounters influenced and characterized his life from then on; they formed the makings of the person he would become.

Boy George came to learn that the natural environment of the varied Cornish seasons – the world that enveloped him each day – was full of surprising, at times tasty riches. He loved to chew the bitter-sweet soursob leaf most of the year round, and learnt that juicy wild strawberries came in June, then blackberries in September, with many others in between: purple damsons, juicy red cherries, delicious hairy gooseberries (perhaps his favourite). All there to sample: a succession of free and flavoursome feasts.

The humble primrose, an early reminder of Spring after the Winter dark, was a special case in point. George and his aunties came to know the ritual, as each year they combed pasture fields and hedgerows, during daylight hours, collecting the little golden jewels in buckets and baskets. Then later they would sit around the large kitchen table, collating, tying and layering the water-sprinkled bunches in cardboard boxes, well into the dark of evening, ready for dispatch to London on the night-time train. Speed was of the essence; it was essential these tiny ambassadors from Cornwall were still fresh when they reached Covent Garden early the next morning. A window of opportunity to add to their income, which was inadequate at the best of times.

On certain days of the week, enroute to school, George would often clamber up into the cab of a passing vehicle: Tuesday the Dairymaid truck, Thursday the local bread delivery van (with a delicious cream cake from Sid the Breadman to add to his lunchbox). Then occasionally, on the way home, a young man would roar past in a glamorous MG sports car: top down and long blonde hair blowing in the slipstream. George, recognizing the burbling exhaust fast approaching from a distance, would jump up onto the roadside bank, ready to wave to his hero sitting behind the wheel.

“Wow!” he gasped, “If only one day that could be me.” Like almost all boys he loved fast cars and imagined himself in the driving seat as soon as he could get a license when he reached that grand old age of eighteen.

At times, when slightly older, he and his mates would stop off to sample the delights of the village shop – perhaps a tangy sherbet with licorice straw, or massive gob-stopper to regulate the banter – later stopping to play cricket or football (depending on the season that drove their interest) at a sort of crossroads clearing they traversed each day during their homeward journey, and which they all knew so well.

But it was life on the farm he loved the best, which in those days was a self-sustaining existence, with meat and milk, veggies and fruit: all home-grown. Fifty or sixty years later the same farm, whilst still owned and operated by the family – in fact George’s youngest cousin – is now a purpose-driven milk production factory, with the majority of those vital home consumables coming direct from supermarket conglomerates, Asda or Tesco, in the nearby town. In the world of today there is no room and no time for messing with vegetable gardens, or fruit orchards or chickens; time is of the essence, with the cows milked by a robotic machine which cost a small fortune! (or large fortune, dependent on one’s point of view). The farm is now home to roughly twice the number of dairy cows it could boast during George’s childhood, but almost all the side industries have been axed. A wide-angle image might show little change, but in close-up the onlooker is able to see huge differences; an indelible critique of the direction in which the family and the world around them has moved.

But harking back to those early years, when George was a young boy, the steep-valleyed environment was an enthralling world for a child to grow up in. Between school and farm chores, and learning how to make and do things, there was also time for a lot of fun. The farm provided his fertile young mind with a fantasy world, which on one day might involve dam building; stemming the little river as it tumbled through the steep-sided, densely forested, 17-acre wood (which adjoined the farm), then building a raft to traverse his man-made ocean. On another day he might stalk the steep, dense slopes of The Wood, armed with a home-made bow and arrow, looking for rabbits (of which there was a multitude).

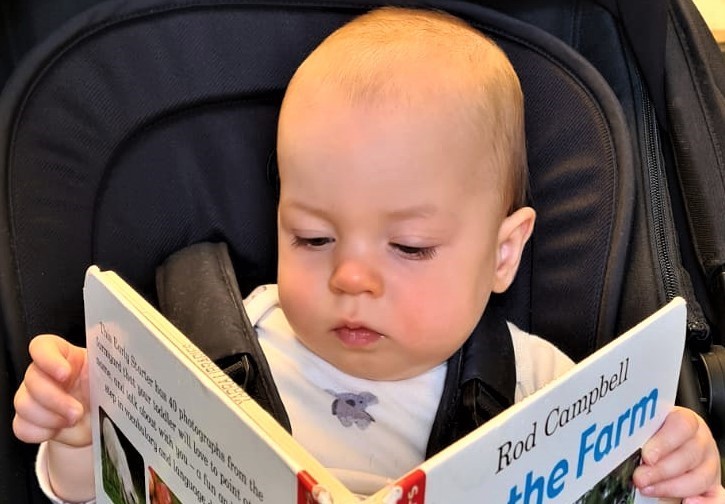

George was Huckleberry Finn in an English setting, Robin Hood in a Cornish forest. At bedtime he was reading children’s adventure books – Enid Blyton’s Famous Five, Swallows and Amazons from Arthur Ransom – which by day were translated into his own make-believe exploits, on and around the farm. He loved to read, and was captivated by turning the pages of fiction into his own world of action-packed adventure.

By the time he was 13 or 14, George knew how to run what was in those days termed a mixed dairy farm, and in fact did just that, when his uncle (and mentor) went on holiday with his wife for the first time in ten years, leaving the teenager in charge of the dairy and all its connected chores. Knowing the array of farm management skills required, involved learning a multitude of tasks: how to work with dogs, catch rabbits, grow lettuce, pickle plums, churn butter, and (unknown to others) manufacture tobacco from dried leaves pressed together in a carpenter’s vice! He was a proficient tractor driver by the time he was ten years old, though had to postpone this skill when the law changed to forbid this until thirteen years!

Many of these accumulated skills would serve him well some years later, when he became immersed in the agricultural world in Australia, culminating in his early thirties with a partnership in a farm management advisory practice. In truth, it seems most likely that the wide range of invaluable farm-based learning experiences significantly influenced George in later life, forming definitive attitudes to the world around, whether England or Australia (or more recently Africa). “Waste not, want not.” was his grandfather’s ever-repeated mantra, and this became an ethos for George too, remaining with him as a guiding light from those early informative years in Cornwall, through to the present day.

———————-

In the mid ‘50s, his family – foreigners to Cornwall as they were called – acquired the adjacent Anglican church rectory, an impressive two-story, eight-bedroom affair; a massive building set within large grounds and including a tythe barn, where in previous times annual taxes had been collected by the church in the form of bags of newly harvested grain. The house and grounds were in serious need of renovation. But dilapidated or not, George loved the labyrinth of rooms, and could imagine ghosts floating along the dusty corridors in the dead of night.

The surroundings of this two-story (former) mansion, which dated from the 18th Century, included an extensive apple orchard that yielded a bounty of large, crisp, wonderfully juicy fruits (hexagonally shaped and nicknamed pigs snouts), as well as a tangled undergrowth of juicy raspberries and thorny blackberries. There was also a tall-treed rookery on one side of the house, with big black nests that dotted the bare branches high above in the winter sky, to which dozens of rooks would return, with their loud caawing sounds, as the short chilly days turned to dusk.

This church rectory had in the past been home to a long line of Anglican vicars, many of whom had disappeared with missionary zeal, off to far-flung corners of the colonies. Each in their turn posted back a veritable stream of letters and cards to their home parish, with stamps bearing elephants from South Africa, kangaroos from Australia, or views from Niagara Falls; so much more enticing than today’s bland emails. This resulted in what became known by the family as The Stamp Room: a reasonably large L-shaped bedroom at the extremity of the upper floor, which was literally ankle-deep in postage stamps. When from time to time, George slipped unnoticed into this treasure trove, to sit like a castaway amongst a virtual ocean of letters and postcards, it seemed an overwhelming task to select and retrieve just a few, to include in his comparatively miniscule stamp album. Like a young child in a sweet shop, it was hard – excruciating almost – to know which of the vast array of goodies on display to sample first.

Years later, following a family feud between his grandfather’s second wife (a fiery Scottish redhead) and the rest of the family, this vast collection of varied papers was shovelled into boxes and old suitcases, to be carried from The Stamp Room and thrown with gay abandon onto a roaring bonfire, outside the front door. How many thousands, or even tens of thousands of pounds were burnt on that fire, is hard to estimate, but in hindsight it did seem a particularly foolish thing to do, whilst the family struggled financially. Looking back, George – even though still very young – felt he had privileged insight into this aspect, because other people hardly ever strayed into the room filled with stamps, which was in an unused and seldom visited corner of the house. He was the only person who had much idea of just how many and how old those stamps were. To add insult to injury he also found out, long after the event, that his toys and other memorabilia from childhood days, such as teddies and board-games, were used to add fuel to the flames. In some ways this obliterated any record of the past for George, which later in life he yearned to turn back to.

Up until the time it was bought by the family, the somewhat abused church rectory had operated as an ecumenical residence, connected to the nearby village church, via a long, private, tree-lined pathway (constructed by one particular pastoral shepherd too shy to meet his flock, in order to facilitate journeys to and from the church in complete privacy!). Prior to its sale, the house was being run by two elderly spinsters: sisters of the last, late vicar. The place suffered such ignominy as wire netting nailed across the grand staircase (to prevent the seventeen pet dogs climbing to the upper floor!), as well as a truckload of empty food cans piled high in the kitchen.

Re-inventing the massive house was a daunting task, but slowly it was converted back into a habitable dwelling, which in time became The Old Rectory guest house, providing bed, breakfast and dinner, for tourists (foreigners from the English mainland who dared to cross the River Tamar), which resulted in much-needed funds for the family’s coffers. George recalls, even as a young lad, being handed a paint-scraper and shown how to bring the old semi-circular wooden staircase, overlooked by a massive stained-glass window, back to its original glory. In today’s it may be criticised as child-labour, in those days it was classed as all-hand-on deck … to get the job done!

Cornwall back then was another world, where tourists were called visitors, or even worse, foreigners (as already mentioned), and the local accent could hardly be deciphered by anyone from lands beyond its borders; those much-disparaged places generally referred to as up country, such as London or Birmingham. How the world has changed since those early post-war days, with innumerable satellite estates of indistinguishable pebble-dash houses, bolted onto chocolate box villages which hail from the 17th Century.

Now, many local businesses are owned and operated by the very foreigners who invaded from the North, and a dual carriageway splits the county in two, facilitating the arrival of multitudinous numbers from those foreign lands. But of course, George and his family will in some ways also remain semi-strangers in this (almost) insular county, for generations to come, and George, having deserted this legacy in the early 1960s, in favour of the land of opportunity down under – like the runner in a 100 metre-relay – can never turn back to retrieve the dropped baton.

And so it was, that not much more than a decade after it was acquired by the family, the rectory and its spacious grounds went back onto the market, to be bought by fresh immigrants from London. George, by that time, well embedded in Australia, was unaware of this turn of events. In hindsight, if he had known, he might well have moved to purchase the place he loved so much. It represented the formative years of his childhood and was sold, as people say, for a song: in fact, probably for much less than the worth of the stamps that were burnt on the bonfire, a few months before it went onto the market! Today, in this 21st Century, it is a thriving hotel worth fifty times the amount it sold for, in those long-gone days of Ford Prefects and flower power.

Returning briefly to that infamous blaze in the rectory grounds – driven by family disagreement – one of the items that fueled the inferno was a collection of A4-sized black and white prints, which featured George, as a young 11-year-old boy, abroad in the British capital. He had been invited to London to stay with a family who were regular holiday makers at The Old Rectory during the summer months. There, he had toured the sights of London with his friend Johnny, the family’s young son, and the boy’s father, a professional photographer, who took a range of glorious and extremely atmospheric, black and white images of the two pals, at sites such as Tower Bridge, Trafalgar Square and the footbridge in St James’s Park looking towards Buckingham Palace. Two boys out and about in the capital on a misty, late summer’s morning. Priceless images of London towards the end of the 1950s, perhaps of more intrinsic value to George than all the stamps or teddy bears that were cast to the flames on that day in Cornwall!

George recalls those early days in the West Country

“My first village school was a small affair with three classes and about seventy kids. The teacher in the lower composite class of five-to-seven-year-olds – a local lass fresh from college – taught me in her first year, and (as it transpired) my eldest daughter, in her final class, forty years later! The headmaster, Mr. Bishop, took the senior class; also a merged group of nine to eleven-year-olds. I used to marvel at the way bulbous blue veins stood out like small wriggly snakes on the back of his hands. In the end it all turned out well. I passed the notorious 11+ exam and moved on to grammar in the nearby town, along with my best friend Dennis. We were the only two students to do so that year. Later, after I escaped being expelled from the grammar school by emigrating, Dennis was already on an upward trajectory to becoming a pillar of the community: two different characters with completely disparate destinies.

My uncle John (or brother as I knew him to be then) was twelve years my senior. He was short and built like a small tank; in comparison I was tall and lanky (anyone looking at us might have wondered about our supposed joint heritage). Despite all that, we had the same sense of humour, or maybe it was a generational thing and many people had that same perception: a symptom of the times, not particularly related to individuals. It was the late 1950s and incredible though it seems now, The Old Rectory had only just been connected to the mainline electricity grid (gas and water came even later). For the first few years we used gas lighting, and I was often tasked with the chore of lighting the ‘tilley lamp’, as the dark came down.

I have visions of them digging these enormous holes to support the electricity poles, then not long after, the steep bitumen road running past the place, being demolished (twice) and rendered virtually unusable for months, to provide for the laying of, first water, then gas pipes. Telephone poles and wires, I think, had been installed some years before. I remember in later years thinking back to those times and smiling when I read about some unfortunate street in Glasgow being dug up for a record ninety-sixth time!

After walking home from the village school, a mile or so down the road, and in the fading winter’s light, unless homework took precedence, it was usually my job to help with the late afternoon milking. More-often-than-not, towards the end of the routine, the topic around the cows and in the attached milk-cooling area, would come around to BBC radio, and in particular, which programme we would listen to, after ‘tea’ that evening (tea being the colloquial term for the evening meal).

So after scrambling up the steep hillside from dairy at the bottom to rectory at the top, we would sit down to a meal in the kitchen, served up by John’s wife, June. This was a large kitchen, with a Rayburn wood-fired cooking stove, which burnt constantly 24/7, through the colder months. There was an old dark brown, bakelite radio on the kitchen bench, and at the allotted time my uncle (then known to me as brother) would tune the dial, the sign for each of us to pull up a chair on either side, where we stayed with ears almost glued to the set for the next thirty minutes. I can never forget the introduction to our favourite ‘Hancock’s Half Hour’: the short lead-in tune, then building up to the … ‘H – H – H – Hancock’s Half Hour’ signature, from the master himself! Tony Hancock was brilliant, but of course he was by no means alone; there was a formidable supporting cast: Sid James, Hattie Jaques, Bill Kerr, John Le Mesurier; voices all still there, in my memory, decades later. I was to begin copying the nasal Aussie drawl of Bill Kerr, just a few years later, but at the time of listening was of course quite unaware of what the future held.

There were many other half-hour radio shows, which all seemed to hit similar ‘funny bones’ for my uncle and I: ‘Beyond our Ken’, ‘Take it from Here’, ‘The Goons’, peopled by some of the Hancock-crew and other well-known playhouse stars of the day. Whether or not they would have the same effect on the hi-tech public of today, as they did in the 50s and 60s, is doubtful; the world has moved on since then. But I still think many would raise a bit of a smile on hearing that line delivered by Hancock in the recognized trademark manner, as part of his most famous ‘Blood Donor’ sketch: ‘It may be just a smear to you mate, but it’s life and death to some poor wretch!’

Not long after the dawn of electricity, it was the turn of television to arrive in our house: a small cream box, with a bubble shaped screen. The image was black and white of course and tended to alternate between fuzzy picture with buzzy sound, and total snowstorm. Some friends in the village had been the first to get a TV, a few months earlier than we did: a larger affair with veneered wood surrounds. I recall, as a nine-year-old boy, sitting on the floral carpet in a packed living room, watching Tommy Steele deliver ‘Singing the Blues’, to commemorate the introduction of ‘the tele’ to our village community on that first Saturday night. At the time it was an exhilarating experience!

But somehow television never quite captured the early magic of those comedy half-hours on BBC radio. ‘Hancock’s Half Hour’ transferred to television and though it was still able to hold an audience, the programme never seemed quite as funny as it had been, before being accompanied by visuals. Psycho-analysts, I guess, would say this is due to the power of our imagination: if we can’t actually see it, then what we hear can conjure up any amount of inspired and improbable images in our fertile minds.

A short while later I do remember when television came more into vogue for me. By that stage, a friend of mine – a neighbouring farmer’s son – had acquired a bike and he would ‘dink’ me home from the village school, at hair-raising speeds down a long narrow track (tarmacked in the past but considerably overgrown now) set like a mini Grandcanyon between seven-feet high, lush green hedges; a feature of the Cornish countryside. Then with schoolbags tossed on the sofa and a welcome cup of cocoa (brought by our most adorable Aunty Mary), early cowboy films were the order of the late afternoon. Iconic episodes of series such as ‘The Lone ranger’, ‘Champion the Wonder Horse’ and ‘Rawhide’ spring to mind … the latter with an unknown newcomer making his debut: Clint Eastwood!

A few years into my Cornwall idyl it was deemed that I should learn to play the pianoforte. One of my aunts had turned up a piano teacher who was said to be a mistress of the art. This sweet little lady, the image of the perfect grey-haired granny, lived – as I soon found out – in a tiny terraced cottage, that I reached each week after a steep climb up from the river estuary in the Cornish coastal village of Looe. Every Wednesday I jumped down from the school bus and half-walked, half-ran, alongside the boat-strewn river, turning in past the 500-year-old Jolly Sailor pub, then proceeding to climb – huffing and puffing with a laden leather satchel on my back – up the steep, narrow incline to my destination, No. 124, with its cute little flower garden and seaside blue door. It was all picture postcard stuff, to which I was totally oblivious. Each week, at five o’clock, I used the heavy metal knocker to signal my arrival.

The backroom window in the doll’s house offered a glorious view over the river way down below, with perhaps a dozen fishing boats moored to the quay, water glistening in the light of the setting sun. The room was just big enough for a highly-polished black Steinway, candelabras and the whole works, along with a well-worn, flower-patterned armchair, on which – for almost all my many visits there – slept an enormous, and extremely fluffy, black and white cat. There was a piano stool to match, together with a wooden chair, where my tutor Miss Maughan, would sit, cardigan wrapped around her floral dress, craning over my shoulder to discern how much practice I had not done since our previous meeting.

The challenge was two-fold: my elderly tutor grounded in a bygone era, and me at the other extreme, beginning to veer off the rails into non-conforming teenage land. Piano practice came a long way down the hit list, compared to grooving with Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry and Cliff … or even more appropriately in this instance, Jerry Lee Lewis. Endless scales and those early piano pieces – that many pupils probably still face even today – just did not gel with me at that moment in time. Perhaps if I had learnt to play ‘Great Balls of Fire’, being allowed to jump up and down on the keyboard, things might have progressed more rapidly! I possessed the talent and had a musical ear (handed down from my mother), but the simple fact was that for me, there was no magic in the tried-and-true method. Sorry Miss Maughan, I am sure you tried.

So these weekly happenings became something of a torturous hour in the late afternoon sun of summer … or early night time chill of winter. Accordingly, I would trudge back across the bridge in my black school blazer and type-cast cap, proud of my long pants -a sort of ‘Just William’ character (another book which I devoured with glee) – to catch the toy train along the Looe Valley, back to the family farm, and home; each time more and more disillusioned by the whole affair.

This mild mutiny against piano lessons was just the start. By the time The Beatles arrived a few years later, I was anti anything to do with establishment or tradition (as I guess many of a similar age were at that time). But ever since then, I have to admit watching with envy, anyone who emerges from the throng to tinkle the ivories with the ease of a Dudley Moore or Elton John. It’s then that I inwardly reflect on something I could have achieved, but decided to flunk.

Remarkably, about 30 years later I put my younger daughter through similar torture, insisting she be taught the flute by a senior citizen: a lady who was also a stickler for scales and all the accompanying torments. It was déjà vu. Like me, so many years before, my daughter learnt in the sitting room, next to the tutor’s Steinway, with a flowery armchair in the corner. The only difference was the absence of the cat. On collecting her from the lesson one day, I found her in tears; then I was finally awoken by my own experience, and immediately encouraged a shift to learning the cello at her school, with a group of kids the same age. The lesson I learnt from all this, is that we often try to inflict aspects of our own undoing, onto our nearest and dearest.

Life’s daily routine on the farm, in the wood, at the village school; evenings with my uncle by the radio, and bike-riding back to a friend’s farm for afternoon cowboys on TV; those weekly trips for piano lessons along the idyllic Looe valley. All were compounded into one. My history; my story: solid foundations for later life.”